ACCOUNTING CONCEPTS

Fraudulent acts are usually interconnected with money and finances. The fraud examiner must therefore understand the source and flow of financial transactions and how they affect an organization’s accounting records. Additionally, the fraud examiner should have an understanding of both financial terminology and accounting theory.

Accounting Basics

Merriam-Webster.com defines accounting as “the system of recording and summarizing business and financial transactions and analyzing, verifying, and reporting the results” for an enterprise’s decision-makers and other interested parties. The measurement and recording of this data are accomplished through keeping a balance of the accounting equation. The accounting model or accounting equation, as shown below, is the basis for all double-entry accounting:

Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ Equity

By definition, assets consist of the net resources owned by an entity. Examples of assets include cash, receivables, inventory, property, and equipment, as well as intangible items of value such as patents, licenses, and trademarks. To qualify as an asset, an item must (1) be owned by the entity and (2) provide future economic benefit by generating cash inflows or decreasing cash outflows.

Liabilities are the obligations of an entity or outsider’s claims against a company’s assets. Liabilities usually arise from the acquisition of assets or the incurrence of operational expenses. Examples of liabilities include accounts payable, notes payable, interest payable, and long-term debt.

Owners’ equity represents the investment of a company’s owners plus accumulated profits (revenues less expenses). Owners’ equity is equal to assets minus liabilities.

This equation has been the foundation of accounting since Luca Pacioli developed it in 1494. Balance is essential to this equation. If a company borrows from a bank, cash (an asset) and notes payable (a liability) increase to show the receipt of cash and an obligation owed by the company. Since both assets and liabilities increase by the same amount, the equation stays in balance.

Accounts and the Accounting Cycle

The major components of the accounting equation consist of numerous detail accounts. An account is nothing more than a specific accounting record that provides an efficient way to categorize similar transactions. All transactions are recorded in accounts that are categorized as asset accounts, liability accounts, owners’ equity accounts, revenue accounts, and expense accounts. Account format occurs in different ways. The simplest, most fundamental format is the use of a large letter $T$, often referred to as a $T$ account.

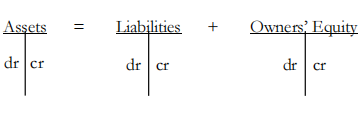

Entries to the left side of an account are debits (dr), and entries to the right side of an account are credits (cr). Debits increase asset and expense accounts, while credits decrease them. Conversely, credits increase liability, owners’ equity, and revenue accounts; debits decrease them. Every transaction recorded in the accounting records has both a debit and a credit, thus the term double-entry accounting. The debit side of an entry always equals the credit side so that the accounting equation remains in balance. The accounting equation, in the form of T accounts, looks like the following:

Fraud investigation often requires an understanding of the debit-and-credit process. For example, a fraud examiner who is investigating the disappearance of $\$ 5,000$ in cash finds a debit in the legal expense account and a corresponding credit in the cash account for $\$ 5,000$, but they cannot find genuine documentation for the charge. The fraud examiner can then reasonably suspect that a perpetrator might have attempted to conceal the theft by labeling the misappropriated $\$ 5,000$ as a legal expense.

Discovering concealment efforts through a review of accounting records is one of the easier methods of detecting internal fraud; usually, one needs only to look for weaknesses in the various steps of the accounting cycle. Legitimate transactions leave an audit trail. The accounting cycle starts with a source document such as an invoice, check, receipt, or receiving report. These source documents become the basis for journal entries, which are chronological listings of transactions with their debit and credit amounts. Entries are made in various accounting journals. These entries are then posted to the appropriate individual general ledger accounts. The summarized account amounts become the basis for a particular period’s financial statements.

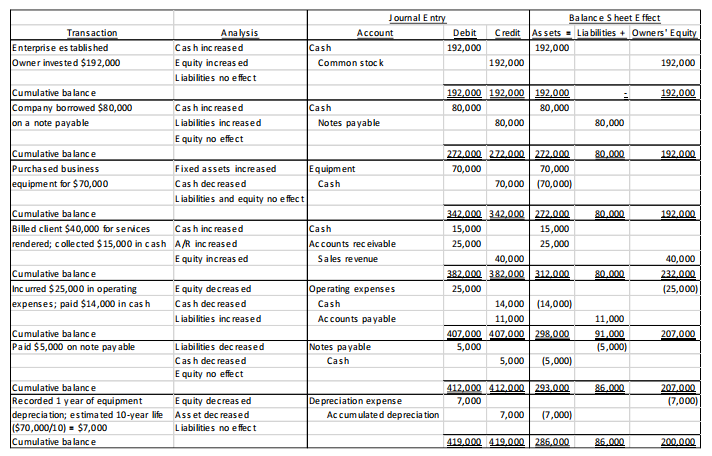

To help explain how transactions affect the financial statements, this flow of transactional information through the accounting process is illustrated below, followed by examples of typical accounting transactions:

Journal Entries

As transactions occur, they are recorded in a company’s books via journal entries. Each journal entry serves as a record of a particular transaction and forms an audit trail that can be retraced later to obtain an understanding of a company’s operations. Journal entries that are not prompted by a transaction, called adjusting journal entries, are also made at the end of a reporting period for items such as depreciation expense and accounts receivable write-offs.

EXAMPLE

XYZ Company completed the following transactions during its first year of operations, 20XX.

Accounting Methods

There are two primary methods of accounting: cash basis and accrual basis. The main difference between the two methods is the timing in which revenue and expenses are recognized.

Cash-Basis Accounting

Cash-basis accounting involves recording revenues and expenses based on when a company receives or pays out cash. For example, sales are recorded when a company receives cash payment for goods, regardless of when the goods are delivered. If a customer purchases goods on credit, the company does not record the sale until the cash is received for the sale. Likewise, if a customer prepays for a sale, the company records the sales revenue immediately, rather than when the goods are given to the customer. The process is the same with expenses: The expenses are recorded when paid, without consideration to the accounting period in which they were incurred.

The key advantage of cash-basis accounting is its simplicity-the only thing its accounting system must track is cash being received or paid. Thus, cash-basis accounting is often used by individuals or small businesses. Using this method makes it easier for companies to track their cash flow. However, a company might decide to delay paying some expenses so they are not recorded in the current accounting period under this method, which results in an artificially inflated bottom line. A major disadvantage of cash-basis accounting is that cash-rich companies might be able to overstate the financial health of their company by having large amounts of unrecorded accounts payable that exceed the cash balance in their accounting records.

Accrual-Basis Accounting

Accrual-basis accounting requires revenues to be recorded when they are earned (generally, when goods are delivered or services are rendered to a customer), without regard to when cash exchanges hands. Expenses are recorded in the same period as the revenues to which they relate. For example, employee wages are expensed in the period during which the employees provided services, which might not necessarily be the same period in which they are paid.

Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) mandate the use of accrual-basis accounting. Accrual-basis accounting records accounts receivable for money that has yet to be received from customers and records accounts payable for purchases made on credit. This accounting method provides immediate feedback to companies on their expected cash inflows and outflows, which makes it easier for them to manage their current resources and efficiently plan for the future. When companies recognize economic events by matching their revenues with the expenses that directly relate to those revenues, it provides a more accurate representation of their financial situation.

Financial Statements

The results of the accounting cycle are summarized in consolidated reports, or financial statements, that present the financial position and operating results of an entity. It is important to have a basic understanding of how financial statements work because they are often the means through which fraud occurs.

Financial statements are presentations of financial data and accompanying notes prepared in conformity with either generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)—such as International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) or a country’s specific accounting standards—or some other comprehensive basis of accounting.

The following is a list of typical financial statements:

- Statement of financial position (balance sheet)

- Statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income for the period (income statement)

- Statement of changes in owners’ equity or statement of retained earnings

- Statement of cash flows

Financial statements might also include other financial data presentations, such as:

- Statement of assets and liabilities that does not include owners’ equity accounts

- Statement of revenue and expenses

- Summary of operations

- Statement of operations by product lines

- Statement of cash receipts and disbursements

- Prospective financial information (forecasts)

- Proxy statements

- Interim financial information (e.g., quarterly financial statements)

- Current value financial presentations

- Personal financial statements (current or present value)

- Bankruptcy financial statements

Other comprehensive bases of accounting include:

- Government or regulatory agency accounting

- Tax-basis accounting

- Cash receipts and disbursements, or modified cash receipts and disbursements

- Any other basis with a definite set of criteria applied to all material items, such as the price-level basis of accounting

Consequently, the term financial statements includes almost any financial data presentation prepared in accordance with GAAP or another comprehensive basis of accounting. Throughout this section, the term financial statements will include the aforementioned forms of reporting financial data, including the accompanying footnotes and management’s discussion. For most companies, however, a full set of financial statements comprises a statement of financial position (balance sheet), a statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income (income statement), a statement of changes in owners’ equity or a statement of retained earnings, and a statement of cash flows, as well as the supplementary notes to the financial statements.

Therefore, fraud examiners should be familiar with the purpose and components of each of these financial statements.

Balance Sheet

The balance sheet, or statement of financial position, shows a snapshot of a company’s financial situation at a specific point in time, generally the last day of the accounting period. The balance sheet is an expansion of the accounting equation, Assets $=$ Liabilities + Owners’ Equity. That is, it lists a company’s assets on one side and its liabilities and owners’ equity on the other side. The nature of the accounting equation means that the two sides of the statement should balance.

The following balance sheet, derived from the journal entries in the aforementioned example, shows the financial position of XYZ Company on the last day of its first year of operations.

XYZ Company

Balance Sheet

December 31, 20XX

| Assets | Liabilities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Assets | Current Liabilities | |||

| Cash | \$ 198,000 | Accounts Payable | \$ 11,000 | |

| Accounts Receivable | 25,000 | Total Current Liabilities | \$ 11,000 | |

| Total Current Assets | \$ 223,000 | |||

| Long-Term Liabilities | ||||

| Fixed Assets | Notes Payable | 75,000 | ||

| Equipment | 70,000 | Total Long-Term Liabilities | 75,000 | |

| Less: Accumulated | ||||

| Depreciation | $(7,000)$ | Total Liabilities | 86,000 | |

| Total Fixed Assets | 63,000 | |||

| Owners’ Equity | ||||

| Common Stock | 192,000 | |||

| Retained Earnings | 8,000 | |||

| Total Owners’ Equity | 200,000 | |||

| Total Assets | \$ 286,000 | Total Liabilities and Equity | \$ 286,000 |

As mentioned previously, assets are the resources owned by a company. Generally, assets are presented on the balance sheet in order of liquidity, or how soon they are expected to be converted to cash. The first section on the assets side, current assets, includes all those assets that are expected to be converted to cash, sold, or used up within one year. This category usually includes cash, accounts receivable (the amount owed to a company by customers for sales on credit), inventory, and prepaid items. Following the current assets are the long-term assets, or those assets that will likely not be converted to cash within one year, such as fixed assets (e.g., land, buildings, equipment) and intangible assets (e.g., patents, trademarks, goodwill). A company’s fixed assets are presented net of accumulated depreciation, an amount that represents the cumulative expense recorded to reflect the expected decline of a company’s property from normal use. Likewise, intangible assets are presented net of accumulated amortization, an amount that represents the collective expense taken for declines in value of the intangible property.

Liabilities are presented in order of maturity. Like current assets, current liabilities are those obligations that are expected to be paid within one year, such as accounts payable (the amount owed to vendors by a company for purchases on credit), accrued expenses (e.g., taxes payable or salaries payable), and the portion of long-term debts that will come due within the next year. Those liabilities that are not due for more than a year are listed under the heading long-term liabilities. The most common liabilities in this group are bonds, notes, and mortgages payable. The total balance of the note payable is listed under long-term liabilities on XYZ Company’s balance sheet, indicating that it does not have to make any payments on the note during the next year. However, if a $\$ 5,000$ payment is required during the next year, the company will have to reclassify $\$ 5,000$ of the note balance to the current liabilities section and show the remaining $\$ 70,000$ as a long-term liability. This adjustment would not change the total amount of the outstanding liability that was shown-all $\$ 75,000$ would still appear on the balance sheet—but it would allow financial statement users to know that the company had an obligation to pay $\$ 5,000$ during the next year rather than at some unspecified time in the future.

The owners’ equity in a firm generally represents amounts from two sources-owner contributions (usually referred to as common or capital stock and paid-in capital) and undistributed earnings (usually referred to as retained earnings). The balance in the capital stock account increases when the owners of a company invest in it through the purchase of company stock. The retained earnings balance increases when a company has earnings and decreases when a company has losses. The retained earnings account is also decreased when earnings are distributed to a company’s owners in the form of dividends. XYZ Company’s balance sheet shows that the company’s owners have contributed $\$ 192,000$ to the company and that the company has retained $\$ 8,000$ of earnings as of December 31, 20XX.

Income Statement

Whereas the balance sheet shows a company’s financial position at a specific point in time, the income statement, or statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income, details how much profit (or loss) a company earned during a period of time, such as a quarter or a year. The accounts reflected on the income statement are temporary; at the end of each fiscal year, they are reduced to a zero balance (closed), with the resulting net income (or loss) added to (or subtracted from) retained earnings on the balance sheet.

The following is the income statement for XYZ Company for its first year of operations based on the sample transactions previously listed.

XYZ Company

Income Statement

For the Year Ended December 31, 20XX

Revenue

Net Sales $\$ 400,000$

Less: Cost of Goods Sold $\underline{250,000}$

Gross Profit $\$ 150,000$

Operating Expenses

Payroll 97,000

Supplies 4,000

Utilities 19,000

Taxes 15,000

Depreciation $\underline{7,000}$

Total Operating Expenses $\underline{142,000}$

Net Income $\underline{\$ 8,000}$

Two basic types of accounts are reported on the income statement—revenues and expenses. Revenues represent amounts received from the sale of goods or services during the accounting period. Most companies present net sales or net service revenues as the first line item on the income statement. The term net means that the amount shown is the company’s total sales minus any sales refunds, returns, discounts, or allowances. Conversely, gross revenues refer to the company’s total sales during the accounting period before any deductions are made.

From net sales, an expense titled cost of goods sold or cost of sales is deducted. Regardless of the industry, this expense denotes the amount a company spent (in past, present, and/or future accounting periods) to produce the goods or services that were sold during the current period. For a company that manufactures goods, cost of goods sold signifies the amount the company spent on materials, labor, and overhead expenses to produce the goods that were sold during the accounting period. For a merchandise reseller, this expense is the amount the company has paid to purchase the goods that were resold during the period. For a service company, the cost of sales is typically the amount of salaries paid to the employees who performed the services that were sold. The difference between net sales and cost of goods sold is called gross profit or gross margin, which represents the leftover amount from sales to pay the company’s operating expenses.

Operating expenses are those costs that a company incurs to support and sustain its business operations. Generally, these expenses include items such as advertising, management’s salaries, office supplies, repairs and maintenance, rent, utilities, depreciation, interest, and taxes. Accrual accounting requires that these items be included on the income statement in the period in which they are incurred, regardless of when they are paid.

A company’s net profit (also known as net income or net earnings) for the period is determined after subtracting operating expenses from gross profit. If a company’s total expenses were greater than its total revenues and the bottom line is negative, then it had a net loss for the period. Commonly, a profitable company will distribute some of its net income to its owners in the form of dividends. Whatever income is not distributed is transferred to the retained earnings account on the balance sheet. In the case of XYZ Company, net income for the year was $\$ 8,000$. The company did not distribute any of these earnings, so the total amount $\$ 8,000$ —is shown on the balance sheet as retained earnings. If the company is also profitable during its next year of operations, any net income that is not distributed as dividends will be added to the $\$ 8,000$ balance in retained earnings. If expenses outperform revenues and XYZ Company shows a loss for its second year, the loss will be deducted from the $\$ 8,000$ retained earnings balance at the end of the second year.

To summarize, the income statement ties to the balance sheet through the retained earnings account as follows:

Statement of Changes in Owners’ Equity

The statement of changes in owners’ equity details the changes in the total owners’ equity amount listed on the balance sheet. Because it shows how the amounts on the income statement flow through to the balance sheet, it acts as the connecting link between the two statements. The balance of the owners’ equity at the beginning of the year is the starting point for the statement. The transactions that affect owners’ equity are listed next and are added together. The result is added to (or subtracted from, if negative) the beginning-of-the-year balance, which provides the end-of-the-year balance for total owners’ equity.

The statement of changes in owners’ equity for XYZ Company would appear as follows:

XYZ Company

Statement of Changes in Owners’ Equity

For the Year Ended December 31, 20XX

Owners’ equity, January 1, 20XX

Investment by owners during the year

Net income for the year

Increase in owners’ equity

Owners’ equity, December 31, 20XX

\$ –

\$ 192,000

$\underline{8,000}$

$\underline{200,000}$

$\$ 200,000$

XYZ Company completed two types of transactions that affected the owners’ equity during 20XX: the $\$ 192,000$ invested by the company’s shareholders, and the revenue and expenses that resulted in the net income of $\$ 8,000$. Had the company distributed any money to the shareholders in the form of dividends, that amount would be listed as a subtraction on the statement of changes in owners’ equity as well. Notice that the $\$ 8,000$ ties directly to the bottom line of the income statement, and the $\$ 200,000$ owners’ equity ties to the total owners’ equity amount on the balance sheet.

Some companies present a statement of retained earnings rather than a statement of changes in owners’ equity. Similar to the statement of changes in owners’ equity, the statement of retained earnings starts with the retained earnings balance at the beginning of the year. All transactions affecting the retained earnings account are then listed and added to the beginning balance to arrive at the ending balance in the retained earnings account. The following is an example of the statement of retained earnings for XYZ Company:

XYZ Company

Statement of Retained Earnings

For the Year Ended December 31, 20XX

Retained earnings, January 1, 20XX \$ –

Net income for the year $\quad \$ 8,000$

Increase in owners’ equity $\quad \underline{8,000}$

Retained earnings, December 31, 20XX $\quad \$ \underline{8,000}$

Statement of Cash Flows

The statement of cash flows reports a company’s sources and uses of cash during the accounting period. This statement is often used by potential investors and other interested parties in tandem with the income statement to determine a company’s true financial performance during the period being reported. The nature of accrual-basis accounting allows (and often requires) the income statement to contain many noncash items and subjective estimates that make it difficult to fully and clearly interpret a company’s operating results. However, it is much harder to falsify the amount of cash that was received and paid during the year, so the statement of cash flows enhances the financial statements’ transparency.

The following is the statement of cash flows for XYZ Company:

| XYZ Company | ||

| Statement of Cash Flows—Direct Method | ||

| For the Year Ended December 31, 20XX | ||

| Cash flows from operating activities | ||

| Cash received from customers | $ 15,000 | |

| Cash paid for merchandise | $(14,000) | |

| Net cash flows from operating activities | $ 1,000 | |

| Cash flows from investing activities | ||

| Cash paid for purchase of equipment | $(70,000) | |

| Net cash flows from investing activities | $(70,000) | |

| Cash flows from financing activities | ||

| Cash received as owners’ investment | 192,000 | |

| Cash received from issuing note payable | 80,000 | |

| Cash paid on note payable | $(5,000) | |

| Net cash flows from financing activities | 267,000 | |

| Increase in cash | 198,000 | |

| Cash balance at the beginning of the year | 0 | |

| Cash balance at the end of the year | $ 198,000 |

The statement of cash flows is broken down into three sections: cash flows from operating activities, cash flows from investing activities, and cash flows from financing activities.

Cash Flows from Operations

The cash flows from operations section summarizes a company’s cash receipts and payments arising from its normal business operations. Cash inflows included in this category commonly consist of payments received from customers for sales, and cash outflows include payments to vendors for merchandise and operating expenses and payments to employees for wages.

This category can also be summarized as those cash transactions that ultimately affect a company’s operating income; therefore, it is often considered the most important of the three cash flow categories. If a company continually shows large profits per its income statement, but cannot generate positive cash flows from operations, then questionable accounting

practices might be the cause. On the other hand, net income that is supported by positive and increasing net cash flows from operations generally indicates a strong company.

There are two methods of reporting cash flows from operations. In the previous example, XYZ Company’s statement of cash flows is presented using the direct method. This method lists the sources of operating cash flows and the uses of operating cash flows, with the difference between them being the net cash flow from operating activities.

In contrast, the indirect method reconciles net income per the income statement with net cash flows from operating activities; that is, accrual-based net income is adjusted for noncash revenues and expenses to arrive at net cash flows from operations. The following is an example of XYZ Company’s cash flows from operations using the indirect method:

XYZ Company

Statement of Cash Flows-Indirect Method

For the Year Ended December 31, 20XX

Cash flows from operating activities

Net income, per income statement

$\$ 8,000$

Add: Depreciation

$\$ 7,000$

Increase in accounts payable

11,000

18,000

26,000

Subtract: Increase in accounts receivable $(25,000)$

(25,000)

Net cash flows from operating activities

1,000

Note that the net cash flows from operating activities is the same amount-in this case, $\$ 1,000$-regardless of the method that is used. The indirect method is usually easier to compute and provides a comparison of a company’s operating results under the accrual and cash methods of accounting. As a result, most companies choose to use the indirect method, but either method is acceptable.

Cash Flows from Investing Activities

Cash inflows from investing activities usually arise from the sale of fixed assets (e.g., property and equipment), investments (e.g., the stocks and bonds of other companies), or intangible

assets (e.g., patents and trademarks). Similarly, cash outflows from investing activities include any cash paid for the purchase of fixed assets, investments, or intangible assets.

Cash Flows from Financing Activities

Cash flows from financing activities involve the cash received or paid in connection with issuing debt and equity securities. Cash inflows in this category occur when a company sells its own stock, issues bonds, or takes out a loan. A company’s cash outflows from financing activities include paying cash dividends to shareholders, acquiring shares of its own stock (called treasury stock), and repaying debt.

The total cash flows from all three categories are combined to determine the net increase or decrease in cash for the year. This total is then added to or subtracted from the cash balance at the beginning of the year to determine the cash balance at the end of the year, which connects back to the amount of cash reported on the balance sheet.

Users of Financial Statements

Financial statement fraud schemes are most often perpetrated by management against potential users of the statements. Financial statement users include company ownership and management, lending organizations, investors, regulatory agencies, vendors, and customers. The production of truthful financial statements has an important role in an organization’s continued success. However, fraudulent statements can be used for several reasons. The most common use is to bolster an organization’s apparent success from the standpoint of potential and current investors. (For more information, see the chapter on “Financial Statement Fraud” in this section of the Fraud Examiners Manual.)

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

In preparing financial statements, management, accountants, and auditors are charged with following the relevant standardized financial reporting practices known as generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). GAAP are the rules by which a company’s financial transactions are recorded into their appropriate account classifications and properly reported as part of the entity’s financial statements.

Historically, each country has promulgated its own GAAP, which has led to a worldwide divergence of accounting practices. It has also contributed to some difficulties in comparing the financial performance of companies in different countries, as well as financial reporting

challenges for multinational entities. Consequently, accounting standard-setters have been working toward a uniform set of accounting standards to enhance the transparency and comparability of financial reporting, facilitate cross-border commerce, and encourage international investment. The resulting International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) has been adopted as the source of GAAP for reporting companies in many countries. However, some countries, such as the United States, have retained their own set of accounting standards that form GAAP for reporting companies in those jurisdictions. Currently, there is not a universally accepted accounting recording and reporting system in existence.

Publicly traded companies must adhere to the specific financial reporting practices of their jurisdiction, which differ among regions. While U.S. GAAP and IFRS are some of the most commonly used accounting frameworks, other countries have their own form of GAAP that might contain different standards. IFRS is considered more of a principle-based accounting framework, whereas U.S. GAAP is known to be more of a rules-based accounting framework. Proponents of IFRS say that a principle-based accounting system better captures an entity’s true economic situation.

For information regarding U.S. GAAP, see the content on “Generally Accepted Accounting Principles” in the “Supplemental Regional Information” section of this chapter on fraudexaminersmanual.com.

International Financial Reporting Standards

The IFRS Foundation was formed in 2001 with the goal of developing “a single set of high quality, understandable, enforceable, and globally accepted [reporting standards] through its standard-setting body, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB).” For each accounting function, the IASB looks for the most appropriate principle for how transactions should be accounted for, or the most suitable method of reporting the results.

According to an analysis on the use of IFRS throughout the world, there are currently 157 international jurisdictions that permit or require the use of IFRS for domestic reporting, and 86 of those permit or require the use of specifically designed international accounting requirements tailored to small- and medium-sized entities.

Qualitative Characteristics of Useful Financial Information

Financial reports provide information about the reporting entity’s economic resources, claims against the reporting entity, and the effects of transactions and other events and conditions

that change those resources and claims. If financial information is to be useful, it must be relevant and faithfully represent what it purports to represent. The usefulness of financial information is enhanced by the following list of qualitative characteristics of useful financial information that accountants should use when creating financial statements in accordance with IFRS.

RELEVANCE

Any financial information that might affect a decision made by a user of the financial statements is considered relevant. Financial information is relevant if it has predictive value, confirmatory value, or both. Predictive value is present if the information can be used as an input to processes employed by users to predict future outcomes. Confirmatory value indicates the information provides feedback about previous evaluations.

MATERIALITY

The amount of an item is material if its omission or misstatement would affect the judgment of a reasonable person who is relying on the financial statements. Materiality is an entityspecific aspect of relevance based on the nature or magnitude, or both, of the items to which the information relates in the context of an individual entity’s financial report.

FAITHFUL REPRESENTATION

Financial information must faithfully represent the economic data of the enterprise that it purports to represent. Every effort shall be made to maximize the qualities of perfectly faithful representation: complete, neutral, and free from error. A complete depiction includes all information necessary to understand the data presented. A neutral depiction is without bias in the selection or presentation of financial information. Free from error means there are no material errors or omissions in the financial reporting data and that the process used to produce the reported information has been selected and applied with no errors.

COMPARABILITY AND CONSISTENCY

Users of financial statements base their decisions on comparisons between different entities and on similar information from a single entity for another reporting period. Comparability is the qualitative characteristic that enables users to identify and understand similarities and differences between such items. Information about a company is more useful if it is comparable with similar information about other entities and with similar information about the same entity for another period or another date. Although a single economic

occurrence can be faithfully represented in multiple ways, permitting alternative accounting methods for the same economic occurrence diminishes comparability.

Consistency, although related to comparability, is not the same. Consistency refers to the use of the same methods for the same items, either from period to period within a reporting entity or in a single period across entities. Comparability is the goal; consistency helps to achieve that goal.

However, both comparability and consistency do not prohibit a change in an accounting principle previously employed. An entity’s management is permitted to change an accounting policy only if the change either:

- Is required by a standard or interpretation

- Results in the financial statements providing more reliable and relevant information about the effects of transactions; other events; or conditions on the entity’s financial position, financial performance, or cash flows

The entity’s financial statements must include full disclosure of any such changes.

VERIFIABILITY

Verifiability helps assure users that information is accurate and faithfully represents the financial position of the entity. Verifiability means that different knowledgeable and independent observers could reach consensus, although not necessarily complete agreement, that a particular depiction is a faithful representation.

TIMELINESS

Timeliness means providing information to decision-makers in time to be capable of influencing their decisions. In general, the older the information is, the less useful it is.

UNDERSTANDABILITY

Classifying, characterizing, and presenting information clearly and concisely makes it understandable. However, some economic data are fundamentally complex. Therefore, enough information should be provided about such events so that a reasonable financial statement user can understand what occurred. An entity’s financial statements should include all information necessary for users to make valid decisions and must not mislead them.

GOING CONCERN

A company’s management is required to provide disclosures when existing events or conditions indicate that it is more likely than not that the entity might be unable to meet its obligations within a reasonable period of time after the financial statements are issued. There is an underlying assumption that an entity will continue as a going concern; that is, the life of the entity will be long enough to fulfill its financial and legal obligations. Any evidence to the contrary must be reported in the entity’s financial statements.

Recognition of the Elements of Financial Statements

Recognition is the process of incorporating an item that meets the definition of an element and satisfies the criteria for recognition into the balance sheet or income statement. It involves the depiction of the item in words and by a monetary amount and the inclusion of that amount in the balance sheet or income statement totals. Items that satisfy the recognition criteria should be recognized in the balance sheet or income statement. The failure to recognize such items is not rectified by disclosure of the accounting policies used, nor by notes or explanatory material.

An item that meets the definition of an element should be recognized if:

- It is probable that any future economic benefit associated with the item will flow to or from the entity.

- The item has a cost or value that can be measured with reliability.

THE PROBABILITY OF FUTURE ECONOMIC BENEFIT

The concept of probability is used in the recognition criteria to refer to the degree of uncertainty that the future economic benefits associated with the item will flow to or from the entity. The concept provides for the uncertainty that characterizes the environment in which an entity operates. Assessments of the degree of uncertainty attaching to the flow of future economic benefits are made on the basis of the evidence available when the financial statements are prepared.

For example, when it is probable that a receivable owed to an entity will be paid, it is then justifiable, in the absence of any evidence to the contrary, to recognize the receivable as an asset. For a large population of receivables, however, some degree of non-payment is normally considered probable; hence an expense representing the expected reduction in economic benefits is recognized. This expense is known as bad debt expense, and the corresponding liability is the provision for doubtful debts.

RELIABILITY OF MEASUREMENT

The second criterion for the recognition of an item is that it possesses a cost or value that can be measured with reliability. In many cases, cost or value must be estimated; the use of reasonable estimates is an essential part of the preparation of financial statements and does not undermine their reliability. When, however, a reasonable estimate cannot be made, the item is not recognized in the balance sheet or income statement.

For example, the expected proceeds from a lawsuit might meet the definitions of both an asset and income, as well as the probability criterion for recognition; however, if it is not possible for the claim to be measured reliably, it should not be recognized as an asset or as income; the existence of the claim, however, would be disclosed in the footnotes, explanatory material, or supplementary schedules.

RECOGNITION OF ASSETS

An asset is recognized in the balance sheet when it is probable that the future economic benefits will flow to the entity and the asset has a cost or value that can be measured reliably.

RECOGNITION OF LIABILITIES

A liability is recognized in the balance sheet when it is probable that an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits will result from the settlement of a present obligation and the amount at which the settlement will take place can be measured reliably.

RECOGNITION OF INCOME

Income is recognized in the income statement when an increase in future economic benefit related to an increase in an asset or a decrease of a liability has arisen that can be measured reliably. This means, in effect, that recognition of income occurs simultaneously with the recognition of increases in assets or decreases in liabilities (e.g., the net increase in assets arising on a sale of goods or services or the decrease in liabilities arising from the waiver of a debt payable).

In general, revenue is recognized to depict the transfer of promised goods or services to a customer in an amount that reflects the consideration to which the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for those goods or services. According to accrual accounting, revenue should not be recognized for work that is to be performed in subsequent accounting periods, even though the work might currently be under contract. For a performance obligation

satisfied over time, an entity should select an appropriate measure of progress to determine how much revenue should be recognized as the performance obligation is satisfied.

The procedures normally adopted in practice for recognizing income are applications of the recognition criteria previously discussed. Such procedures are generally directed at restricting the recognition as income to those items that can be measured reliably and have a sufficient degree of certainty.

RECOGNITION OF EXPENSES

Expenses are recognized in the income statement when a decrease in future economic benefit related to a decrease in an asset or an increase of a liability has arisen that can be measured reliably. This means, in effect, that recognition of expenses occurs simultaneously with the recognition of an increase in liabilities or a decrease in assets (e.g., the accrual of employee entitlements or the depreciation of equipment).

Expenses are recognized in the income statement on the basis of a direct association between the costs incurred and the earning of specific items of income. This process, commonly referred to as the matching principle, involves the simultaneous or combined recognition of revenues and expenses that result directly and jointly from the same transactions or other events; for example, the various components of expense making up the cost of goods sold are recognized at the same time as the income derived from the sale of the goods.

When economic benefits are expected to arise over several accounting periods and the association with income can only be broadly or indirectly determined, expenses are recognized in the income statement on the basis of systematic and rational allocation procedures. This is often necessary in recognizing the expenses associated with using up assets such as property, plant, and equipment; goodwill; and patents and trademarks. In such cases, the expense is referred to as depreciation or amortization. These allocation procedures are intended to recognize expenses in the accounting periods in which the economic benefits associated with these items are consumed or expire.

An expense is recognized immediately in the income statement when an expenditure produces no future economic benefits or when, and to the extent that, future economic benefits do not qualify, or cease to qualify, for recognition in the balance sheet as an asset.

Measurement of the Elements of Financial Statements

Several different measurement bases are employed to different degrees and in varying combinations in financial statements. They include the following:

- Historical cost—Assets are recorded at the amount of cash or cash equivalents paid or the fair value of the consideration given to acquire them at the time of their acquisition. Liabilities are recorded at the amount of proceeds received in exchange for the obligation, or in some circumstances (e.g., income taxes), at the amounts of cash or cash equivalents expected to be paid to satisfy the liability in the normal course of business.

- Current (replacement) cost—Assets are carried at the amount of cash or cash equivalents that would have to be paid if the same or an equivalent asset were acquired currently. Liabilities are carried at the undiscounted amount of cash or cash equivalents that would be required to settle the obligation currently.

- Realizable (settlement) value-Assets are carried at the amount of cash or cash equivalents that could currently be obtained by selling the asset in an orderly disposal. Liabilities are carried at their settlement values; that is, the undiscounted amounts of cash or cash equivalents expected to be paid to satisfy the liabilities in the normal course of business.

- Present value-Assets are carried at the present discounted value of the future net cash inflows that the item is expected to generate in the normal course of business. Liabilities are carried at the present discounted value of the future net cash outflows that are expected to be required to settle the liabilities in the normal course of business.

- Fair value-Assets are carried at the price that would be received to sell an asset in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date. Liabilities are carried at the price that would be paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.

The measurement basis most commonly adopted by entities in preparing their financial statements is historical cost. This is usually combined with other measurement bases. For example, inventories are usually carried at the lower of cost or net realizable value; marketable securities can be carried at market value; and pension liabilities are carried at their present value. Furthermore, some entities use the current cost basis as a response to the inability of the historical cost accounting model to deal with the effects of changing prices of nonmonetary assets.

Departures from Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

As with rules for most things, departures from GAAP are sometimes required. It was impossible for GAAP developers to anticipate all circumstances to which the principles are

applied. It can be assumed that adherence to GAAP almost always results in financial statements that are fairly presented. However, the standard-setting bodies recognize that, upon occasion, there might be an unusual circumstance when the literal application of GAAP would render the financial statements misleading. In these cases, a departure from GAAP is the proper accounting treatment.

The question of when it is appropriate to stray from GAAP is a matter of professional judgment; there is not a clear-cut set of circumstances that justifies such a departure. However, departures from GAAP can be justified in the following circumstances:

- There is concern that assets or income would be overstated and expenses or liabilities would be understated (the conservatism constraint requires that when there is any doubt, one should avoid overstating assets and income or understating expenses and liabilities).

- It is common practice in the entity’s industry for a transaction to be reported in a particular way.

- The substance of the transaction is better reflected (and, therefore, the financial statements are more fairly presented) by not strictly following GAAP.

- The results of departure appear reasonable under the circumstances, especially when strict adherence to GAAP would produce misleading financial statements and the departure is properly disclosed.

- If a transaction is considered immaterial (i.e., it would not affect a decision made by a prudent reader of the financial statements), then it need not be reported.

- The expected costs of adherence to GAAP exceed the expected benefits of compliance.

The following modifying conventions give guidance and should be considered when deviating from what is generally acceptable.

Conservatism

The conservatism constraint requires that when there is any doubt, one should avoid overstating assets and income or understating expenses and liabilities. This principle’s intention is to provide a reasonable guideline in a questionable situation. If there is no doubt concerning an accurate valuation, this constraint need not be applied. An example of conservatism in accounting is the use of the lower of cost or net realizable value as it relates to inventory valuation. If a company’s financial statements intentionally violate the conservatism constraint, they could be fraudulent.

Industry Practices and Peculiarities

The peculiarities and practices of an industry (such as banking, investment, and insurance) might warrant selective exceptions to accounting principles if they are infrequent and justifiable. Some differences in accounting also occur in response to legal requirements, such as those entities subject to regulatory controls.

Substance over Form

The economic substance of a transaction determines the accounting treatment, which might differ from the legal treatment. For example, although a lease contract may not transfer property rights, if the true substance of the transaction is a sale, then the lessee should record the transaction as an acquisition and capitalize the property.

Application of Judgment

An accountant may depart from GAAP if the results of departure appear reasonable under the circumstances, especially when strict adherence to GAAP will produce misleading financial statements and the departure is properly disclosed.

Materiality

The amount of an item is material if its omission would affect the judgment of a reasonable person who is relying on the financial statements. The materiality threshold does not mean that immaterial items do not have to be recorded; rather, strict adherence to GAAP is necessary only when the item has a significant effect on the financial statements of an entity. In addition, the aggregate effect of immaterial items must also be considered.

Cost-Benefit

A departure from GAAP is permitted if the expected costs of reporting a transaction in compliance with GAAP exceed the expected benefits of compliance. However, the fact that complying with GAAP would be more expensive or would make the financial statements look weaker is not a reason to use a non-GAAP method of accounting for a transaction.

Leave a Reply